Fifer Grounding

As the saying goes, hindsight is 20/20, and by the end of this story, you too will see.

For five months straight we had been going to Canada for three day weekends. We would leave Kingston Thursday on the 7PM ferry, and pull into Tom Mac shipyard before 10PM. We had a trip down to a science, crossing the border when it was still manned for the evening rush, but after it had passed. We had the home trip timed perfect too, returning on Sunday, unless it was a holiday weekend, in which case we stayed until Monday night.

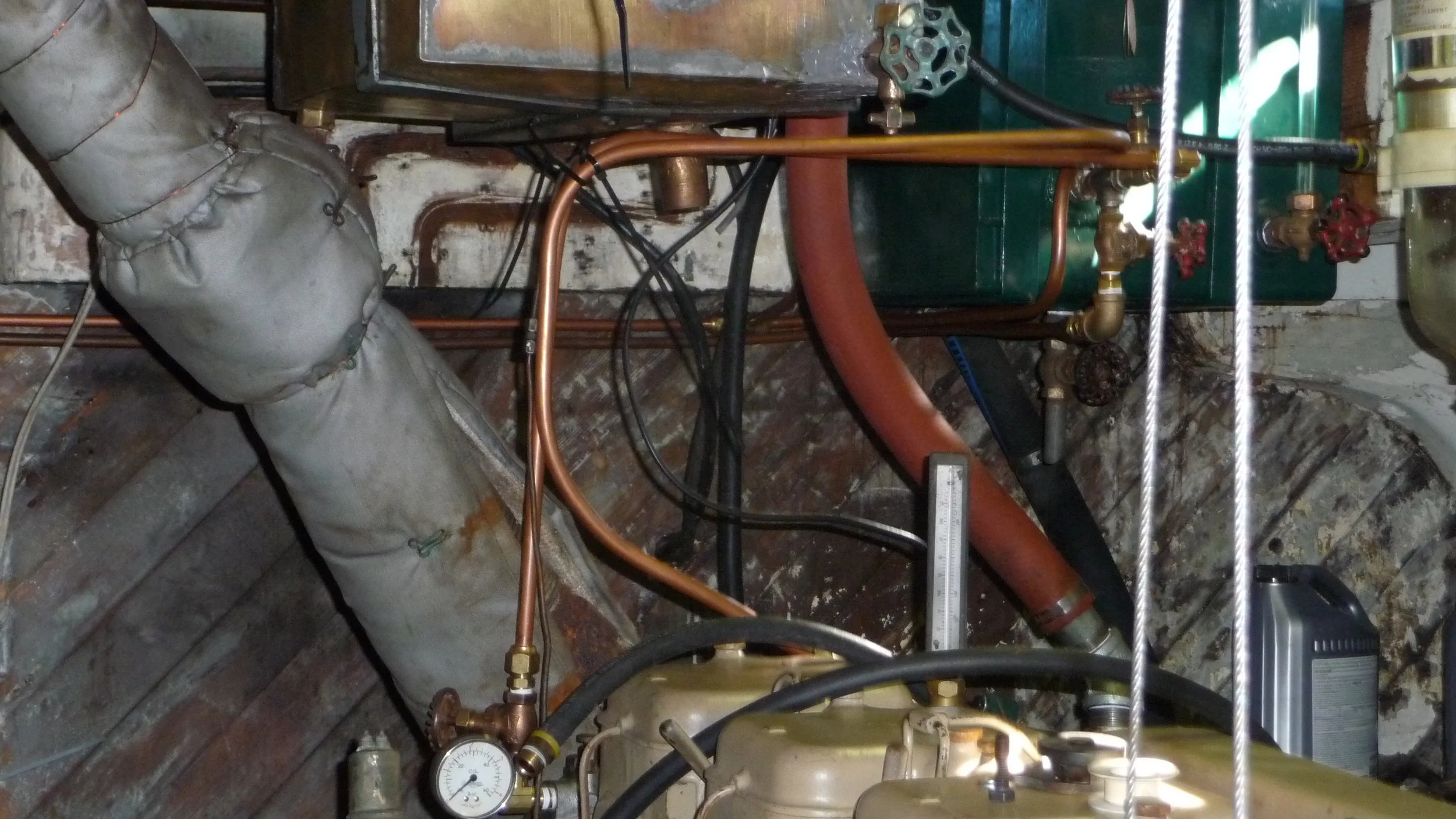

By the end of August we were operational. The engines were running beautifully, and we had done a “fast cruise.” Fast cruise is a shakedown where you test all your systems, including spinning your props, while still tied to the dock. The idea is to get the boat and crew ready for the first underway after an extended refit, by testing machinery and systems, with everyone at their posts.

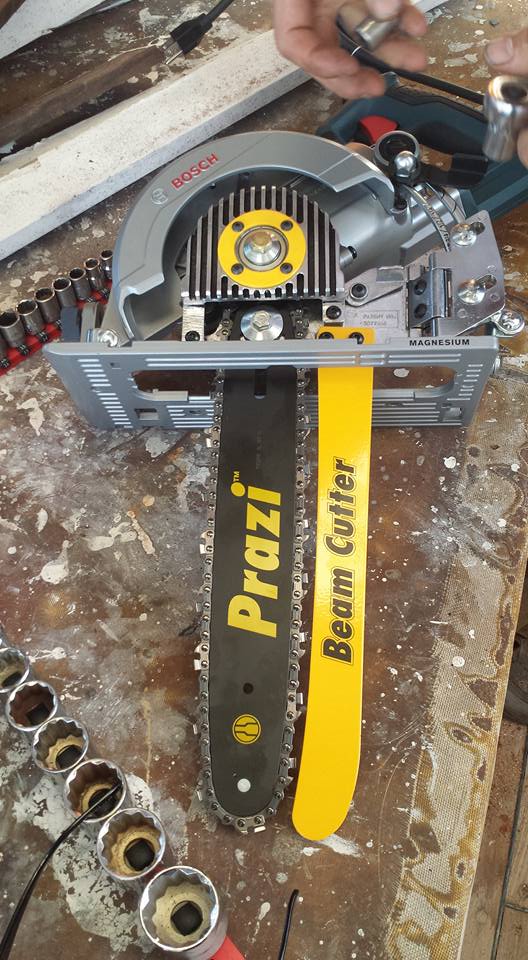

In the days leading up to the planned underway, we had our share of last minute setbacks. The laptop we had all set up and networked for navigation had a bad motherboard, and there were many details like ensuring all of our navigation lights were properly wired. There were adapters to track down to wire the radar, and antennae to mount for the VHF, and paper work to prepare for customs.

There was not a lot of maneuvering room on the North Fork of the Frasier River, so the evening before, on an outgoing tide, we did a “dead stick” move using long lines and the current to pull her out of her slip, and spin her around to the outermost side tie. She was aimed for home, and ready for her voyage.

Not much sleep was had the night of 6 September, and I was up at sunrise on the 7th with my father to finish plumbing the fresh water tanks in the stern. I wanted them filled to trim Fifer as she is a bit bow heavy. By early afternoon everything was ready, and the plan was to head for Deer Harbor, tie up to the customs dock, and clear customs the following morning.

It was a late start, as we headed down the Frasier, but we still wanted to rendezvous with Deerleap, Fifer’s sister, for the trip south, and we knew he was leaving Deer Harbor on the morning of the 8th. I was glad that I did not have to do a lot of maneuvering. I was getting a feel for her fifty eight tons, and she felt and looked great, as we passed joggers and picnickers out in the summer sun, pausing to watch her pass, even if she responded to the wheel more as suggestions before responding.

By the time we made it out to the Straits, it was shaping up to be an amazing sunset. As we got into open water, I gave her more throttle, to start making better time, but the log was still only reading three and a half knots. Ben did some dead reckoning at the chart table, as well as checking the GPS on his phone, and for a third opinion the ships computer. They all confirmed that we were going no faster at the higher RPM. Then Carrie came up from the engine room. “The gear boxes are smoking and smell like burnt oil” she said. She had mentioned that the gearboxes seemed hot while we were transiting the river, which I chalked up to everything wearing in. Now I knew there was something wrong. I throttled back down to 250 RPM, and we did not lose any speed, but the gearboxes started cooling down.

We got a bit of rough chop, and the dingy came loose and swung out on the boom on the Port side. Carrie headed up to secure it, but after nearly going over, and us yelling at her, she came back down to put on a life jacket as I steered Fifer into the swell to calm her out. After she went up the second time to and got the dingy secure, we had a family meeting on the bridge to discuss our situation. We called Boat US, the provider for our tow insurance, like AAA on the water, and they stated that the earliest they could get a tow to us was the next morning, and that it would simplify things considerably if we could clear customs first. Deer Harbor was out of the question, and so our options were either Point Roberts, or beyond that Anacortes. At this point the water had calmed as the sun set, and we continued South. By ten it was obvious that Point Roberts was our best option. We contacted the US Coast Guard, who seemed indifferent, and then the Canadians, who were sympathetic, but had little to offer. I went up on deck to check the windlass, and anchor, as there is sheltered anchorage outside the harbor. I had not run the hydraulics’ to it, but had checked manual operation several weeks before. Now it was frozen, and I tried to work out how I could retrieve the Danforth if I anchored out. Not having knowledge of the type of bottom, nor much experience setting an anchor, and none with Fifer, I resolved to navigate into the customs dock.

I studied the charts, and even pulled up Google earth on my phone to look at the satellite imagery of the entrance. The channel into the harbor runs South to North, but you cannot go straight in as there is a protective rock wall running East West parallel to the shore. To protect the harbor from winter storms blowing from the South. With a twin screw boat making a sharp turn is much easier because you can reverse the screw on the inside of the turn, so despite Fifer’s 58 tons, I figured we could come in slow and easy. We had not taken the time to hook up hydraulics to the gearboxes, so Carrie was going to act as engineman, just as would have been done prior to 1935, when she was the first private yacht fitted with hydraulic shift control from the bridge.

We slowly limped into Point Roberts at 3AM on 8 September 2011 on a high tide. I approached from the West staying to the right to swing wide for the turn. In the spotlight we caught a left arrow sign mounted to a piling mounted in the middle of the channel on the East side. It seemed odd, and I thought no kidding as I turned the wheel full rudder to Port. She started to turn, but it became obvious not fast enough so I throttled down to idle on the Port Engine and yelled down to my engine woman to shift Port to reverse. Ben had actually rigged a set of lights for each gearbox as a hybrid engine order telegraph, and I had switched the toggle just before redundantly ordering the reverse bell, but we were slowly approaching the sign with a turn much too wide. “The gearbox is stuck” she yelled back. I throttled starboard down to idle and ordered Starboard in reverse so we could at least stop. “This gearbox is stuck too!” she yelled back. At this point I practically jumped down the ladder to the hand-wheels, first Port, the Starboard, which I had tested operational just 20 minutes earlier, and sure enough, neither would budge. Climbing back to the bridge, I shut down both engines as we slowly creeped towards the sign. I told Ben to go up to the bow to push off the piling which was now just off the Port Bow. Slowly we inched forward, and I went out on deck with him and my father to try add more muscle to push off the piling that was now about six feet past the bow. It was now obvious we were aground, and looking at the sign that was actually a diamond, bent over by some other boat coming in from the East, I knew why. Shining a light into the water I could see that the piling was stuck in the middle of a rock wash wall, still submerged on the outgoing tide. No amount of pushing would dislodge us, and the tide had turned and was rapidly going out. A seal looked at us from the eel grass in the channel behind, curious about why we would park there. I went back down to the engine room but the hand-wheels would still not budge. Back on deck, I looked around us with my flashlight for something that I could tie off to for leverage to pull us free, and seeing nothing lowered the dingy over to inspect. At the bow, the water level was receding with the stem firmly resting on the rocks. I tried leverage, and pulling with the dingy, but we were now hard aground.

We called Boats US, the US Coast Guard, and the Canadian Coast Guard to inform them of our new situation, with the same results as earlier. Boats US would not have a tow boat to us until 8 AM, the USCG could care less, but the Canadians actually volunteered a boat to come help if they could. About 4 AM the Canadian patrol boat showed up, and after a failed attempt to pull us free, made sure no one was injured, helped make sure that the fuel tanks were secure, and helped set an anchor to the stern to keep the boat from swinging into the channel. They were sympathetic, but we would just have to wait until the next high tide. Checking the tables, the next high, which luckily would be just as high would be in the early afternoon. As we waved goodbye to our Canadian friends, we resolved to get as much sleep as we could, which wasn’t going to be easy, as she was now starting to list.

We might have gotten a couple hours at most before the Boats US tow boat arrived. After ferrying my father, Ben, and Katrianna to the customs dock, which was less than 100 feet away, we discussed our options. Being hard aground is not covered, and their assistance was not going to be cheap. The alternative was that the harbor master would want to put an oil boom around us, even if not one drop of petroleum went into the water, and that would cost $25,000. Fifteen hundred dollars an hour, for the five and a half hours until the next high tide, was obviously a better deal, so we took that option.

As the tide started to come back in, Carrie and I got to work. I dumped the 600 gallons of freshwater in the stern tanks to the bilge, and pumped it overboard. I pulled batteries from the engine room, now at a 40 degree angle to port, and 15 degrees bow to stern, up to the Starboard deck. Ran pumps and hoses, and duct taped vents, battening down all the portholes and hatches on the Port side. Carrie went into the engine room and filled three trash bags with absorbent towels cleaning any and all possible oil from the bilges. If we took any water on and had to run pumps, we did not want even a hint of oil in that water. Slowly the tide crept up towards the Port toe rail.

Sometime during all this, I called Slim Gardner, captain and owner of Deerleap, to ask for assistance. “I can’t tow you, as I have less power than you,” he stated. “I don’t need a tow Slim, I just need someone here with more experience, and sleep than I have,” I replied. “Fair enough, I am almost to Port Townsend but will be there as fast as I can.”

I was standing on the outside the handrails of the Starboard rail. The big electric and gas pumps were rigged, and my son had walked over the now dry wash wall rocks to hand Carrie and I a sandwich my father had bought for us. I watched as the water rose within two inches of the Port toe rail, and as I enjoyed the sandwich, knowing we had done all we could for now, I felt the Fifer pop out of the sand under the stern, as she gained buoyancy. Slowly she started to roll upright, and smiling at Carrie in relief, I looked up to see Deerleap steaming towards us, and looking every bit like the Calvary with her flags flying. We waved and chatted briefly as he maneuvered into the customs dock, and I knew everything was going to be alright.

As Fifer was about to float free of the rocks, I finally got a call back from the USCG. They wanted to get some additional information to complete a report. Ten minutes later I saw why when a USCG helicopter flew over with special cameras to try and detect any oil in the water so that they could fine us. After a couple of passes they flew off empty handed. Considering how much it costs to put a helicopter in the air, I’m sure they were disappointed they could not be more helpful.

Soon Fifer was tied to the dock behind Deerleap. After clearing customs, it was agreed that Slim would give up one of his crew to man Fifer, and that Ben would join him, but would not have duty until after he got some sleep. After paying the Boats US for the grounding, they tied off the lines for the tow, and maneuvered her out of the harbor. We cast lines off of Deerleap, and I sat in the pilothouse with Slim as he followed her out. After a seafood dinner, a shower, and a change into some clean clothes, we climbed into our bunks as Deerleap one (Fifer) and Deerleap two headed home.

Once safely home and rested, I eventually tracked down some original drawings for the gear boxes on a British website Canalboat.org. As soon as I saw the installation diagrams, I knew what had gone wrong. The gearboxes had been installed backwards, and with the thrust bearings in front, and none at the back, the thrust from the props would push the clutches out and cause them to slip above a low idle. How the shop that rebuilt the boxes managed to install the input flange with a different bolt pattern and inside diameter than the output flange, I have yet to figure out. What I have learned in hindsight is that rushing for a deadline, not having full documentation for your equipment, inexperience, and too many loose ends, all in combination can add up to expensive learning experiences. I also learned that under pressure, Carrie and I can rise to the occasion, and take care of business.